Now Vice-Chancellor and Principal at Arts University Bournemouth, Professor Paul Gough is a painter, broadcaster, and writer whose work has been exhibited internationally. His research, which is globally recognised, delves into imagery of war and peace, a consistently rich topic for street artists. He is currently writing his second book on the subject of the ever-elusive Banksy. Here, Paul gives us some insight into his personal reaction to street art through the decades, his fascination with the ‘artist’ at work, and shares some rare snippets from his new book.

NAME: Professor Paul Gough

OCCUPATION: Vice-Chancellor and Principal of Arts University Bournemouth | Writer | Presenter | Painter | Banksy expert

HOMETOWN: Bristol

1. Favourite city for street/urban art?

Bristol in the UK, closely followed by Melbourne, Australia, where I worked for six years.

2. What was the first work of street art you ever saw? How did it make you feel?

CND murals in London during the height of the nuclear disarmament campaign run by the Greater London Council (GLC), and the Cable Street Mural in east London: It made me feel elated that artists could work at such scale, with such passionate ambition, on a par with the great US and Mexican social muralists.

View this post on Instagram

3. Which work of street art has made the deepest impression on you since then?

The light projections by Krzysztof Wodiczko in London, New York and Berlin certainly count as a powerful form of street art; they are transitory creative interventions, political statements that arouse intense interest and stir emotions, while making profound points with limited visual means; the outpouring of cardboard banners and placards created by those who wanted to register their feelings about the toppling of the statue of Edward Colston in central Bristol made a deep impression too.

4. Who is your Street Art hero? Why?

Too many to say, really, and also so few of them are really known except by their street name, their handle. As I’ve reflected on and written so much about Banksy, I’d have to select his/her/their work, though quite if I’d describe the work as heroic or created by an hero is wide open to debate.

5. Should graffiti be decriminalised?

A complicated question for which a yes/no answer would just over-simplify a deeper conversation: there needs to be a debate about what constitutes ‘public art’, ‘street art’, ‘urban artworks’ etc; this is entirely possible but in the present conditions and circumstances (August 2020) culture wars quickly become polarised and the core questions tend to be quickly clouded: Churchill as a statue / Churchill as statesman for example.

6. Artist editions or murals?

Both! Artists, muralists, painters of scale have to subsist too.

7. Who’s the new Banksy?

There are already so many copyists who think they are the new Banksy; that’s fine: after all, ‘pastiche is a form of flattery’ and I saw recently a large Bansky-esque stencil of a policeman spraying the tag ‘This was not done by Banksy’ in Penzance, deepest Cornwall. I guess that might be considered a sort of ‘Cornish pastiche’?

8. Street Art: more art or activism?

Both; they can co-exist and they form a necessary dialogue in our urban realm.

9. If you could invite only 3 guests to your street party who would they be?

Original members of The Jam, preferably with their instruments and a sound system.

10. What would you eat and drink?

A lot of everything.

11. What is your favourite tag?

My son’s, but I can’t fairly reveal its identity.

12. What is your favourite street art festival?

UpFest in Southville and Bedminster in Bristol: slap bang in the middle of where we live.

13. Stencil or freehand?

Both! Why? These are sections from the book I’m currently writing:

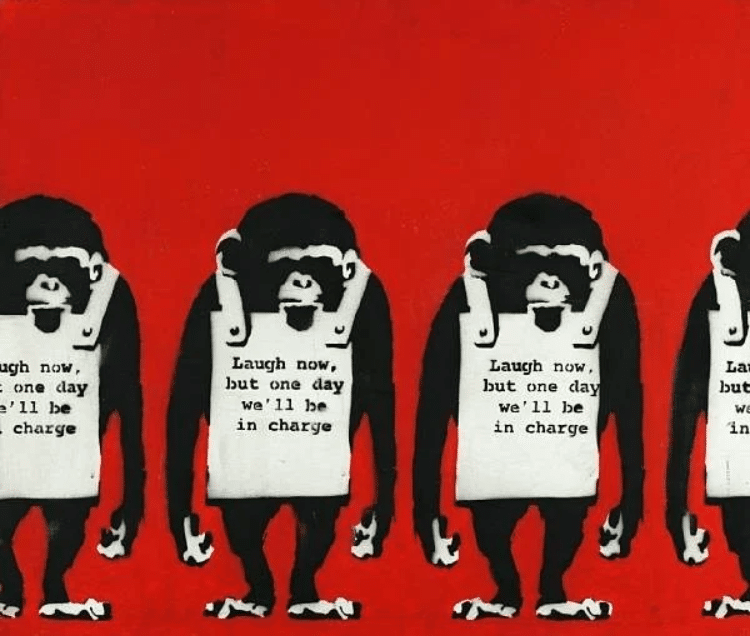

“Banksy has become synonymous with stencilling. He has taken its essential graphic form, grasped its power to evoke countercultural emblems of rebellion, and subverted it to create some of the most popular icons in our contemporary visual culture.”

“Watching a freehand writer at work on a white wall is to witness a body in motion, a choreography of calligraphy; masked, capped, gloved, but with the whole body liberated by the super scale and raw ambition of the big graphic gesture.”

14. Colour or black and white?

Both, because actually both require creative discipline, innovation and practice.

15. Why do you think street art has been growing in popularity over recent decades?

An extract from my new book:

“To some degree the new waves of street art reflect post-modern concerns – playful, variant, politicised – when compared to the stylistically modernist and homogenous language of classic graffiti. If street art is a post-modern form of ‘street speak’ that can send messages from the disenfranchised to the powerful, then its most erudite and combative communicators have become Banksy or Shepard Fairey, who have both opened up the genre of ‘high street irony’.”

16. If you could watch anyone at work who would it be?

Any reputable street artist working from the origination of the idea, the sketch, the provocation through to its fruition on a surface. My book is all about the practice, the doing, and the very practices that are so easily overlooked because the press assume we treat street art as little more than an elaborate ‘whodunnit’.

To watch the artist means I could then answer this question which opens my new book:

“How has it been possible for a solitary street artist to move so rapidly from clandestine hooded tagger to an impresario capable of staging events of global renown? What creative skillsets has it required, and how has Banksy been able to galvanise a team of supporters and makers to realise his extraordinary ambition far outside the mainstream. What lessons for those who practice today as painters, printmakers, sculptors, filmmakers might be gleaned from Banksy’s furtive methods and his management of an ever-morphing but clearly highly skilled and faithful crew of co-workers. Is there any shared learning from his innovative approach to promotion; the way he and his tight team of publicists spread the word without resort to the machinations of conventional marketing, but cannily manipulate professional communication methods, social media, and viral messaging to reach vast audiences and primetime viewing.”

17. Does street art belong in museums?

The walls of the most innovative and democratic museums are already porous, sharing what has formerly been locked ‘inside’ with those who have been ‘outside’; in our digital age we can access entire collections, take tours, share in the conversation. Street art is no different – it has through the step into a shared, dialogic space; museums and galleries can create, educate and develop new audiences and the vernacular language of so much street art has allowed others in; it’s a marvellous innovation. Long may it continue.

What advice do you have for young street artists or enthusiasts just starting out?

Practice, practice, practice. Borrow from the best, unashamedly. Learn the ABC of your preferred pictorial language before you try to say something too bold. Be self-critical, self-disciplined; take your work seriously, but not yourself.

19. What do you think makes street art so appealing to the general public?

Accessibility; democratic; open to all, no ‘turnstile experience’. There is also the aspect of being able to see the work as it is actually being produced . Most Western viewing publics really cherish seeing the practice, processes, the methods and materials of the creative arts. Hence the popularity of gardening, cooking and baking programmes of TV, which aim to lift the lid of the alchemy that underwrites creativity, even in the kitchen.

Professor Paul Gough has kindly shared with Street Art Bio an extract from the opening of his new book:

Banksy

A monograph on the artist in final draft by Paul Gough

In a Western world obsessed by salacious celebrity stories, by ‘kiss and tell’ confessions, conspiracy theories, and the restless prying of red-top journalists, Banksy has largely been viewed through the lens of the ‘whodunnit’, as an individual (but also quite possibly a Collective of Artist-disrupters) who alternates uncomfortably between being hailed a national treasure and folk hero as well as an imposter who has reneged on ‘his’ graffiti roots. An artist who has forsaken street-cred for credit in the bank. Such is the caricature of the elusive ‘scarlet pimpernel’, a can-carrying Robin Hood, the world’s most famous unknown artist.

Yet no one really talks about the art itself, about the practice, the innovative visuals, the extensive and challenging graphic language, nor the extraordinary curatorial and filmic skills that make Banksy one of the most diverse popular practitioners of our time. This book, written by a practising artist, tries to rectify the absence of an appreciation of Banksy as artist.

But it also explores the complicated and interdependent work of artist as sole trader, an individual responsible for every aspect in the creative production line: Ideas originator, materials gatherer, locator of venues, marketing and recording, promotion and intervention, let alone actually making the work – cutting the stencils, devising fonts, gathering and nurturing talent, the complicated processes of fabrication, framing, presentation and, of course, self-critical reflection.

Profile Image painted by Glyn Wyles